|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

The United States Of America National Anthem

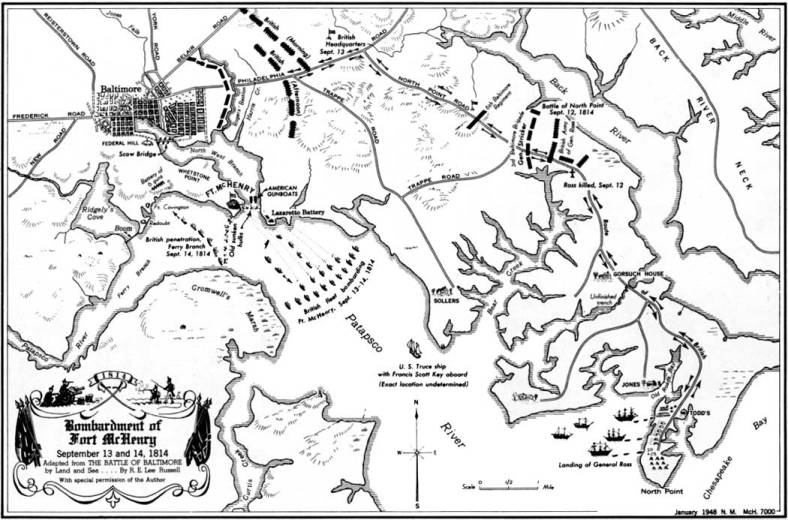

Guarding the entrance to Baltimore harbor via the Patapsco River during the War of 1812, Fort McHenry faced almost certain attack by British forces. Major George Armistead, the stronghold's commander, was ready to defend the fort, but he wanted a flag that would identify his position, and one whose size would be visible to the enemy from a distance. Determined to supply such a flag, a committee of high-ranking officers called on Mary Young Pickersgill, a Baltimore widow who had had experience making ship flags, and explained that they wanted a United States flag that measured 30 feet by 42 feet. She agreed to the job.

Fort McHenry

With the help of her 13-year-old daughter, Caroline, Mrs. Pickersgill spent several weeks measuring, cutting, and sewing the 15 stars and stripes. When the time came to sew the elements of the flag together, they realized that their house was not large enough. Mrs. Pickersgill thus asked the owner of nearby Claggett's brewery for permission to assemble the flag on the building's floor during evening hours. He agreed, and the women worked by candlelight to finish it. Once completed, the flag was delivered to the committee, and Mrs. Pickersgill was paid $405.90. In August 1813, it was presented to Major Armistead, but, as things turned out, more than a year would pass before hostile forces threatened Baltimore. After capturing Washington, D.C., and burning some of its public buildings, the British headed for Baltimore. On the morning of September 13, 1814, British bomb ships began hurling high-trajectory shells toward Fort McHenry from positions beyond the reach of the fort's guns. The bombardment continued throughout the rainy night. Anxiously awaiting news of the battle's outcome was a Washington, D.C., lawyer named Francis Scott Key. Key had visited the enemy's fleet to secure the release of a Maryland doctor, who had been abducted by the British after they left Washington. The lawyer had been successful in his mission, but he could not escort the doctor home until the attack ended. So he waited on a flag-of-truce sloop anchored eight miles downstream from Fort McHenry. During the night, there had been only occasional sounds of the fort's guns returning fire. At dawn, the British bombardment tapered off. Had the fort been captured? Placing a telescope to his eye, Key trained it on the fort's flagpole. There he saw the large garrison flag catch the morning breeze. It had been raised as a gesture of defiance, replacing the wet storm flag that had flown through the night.

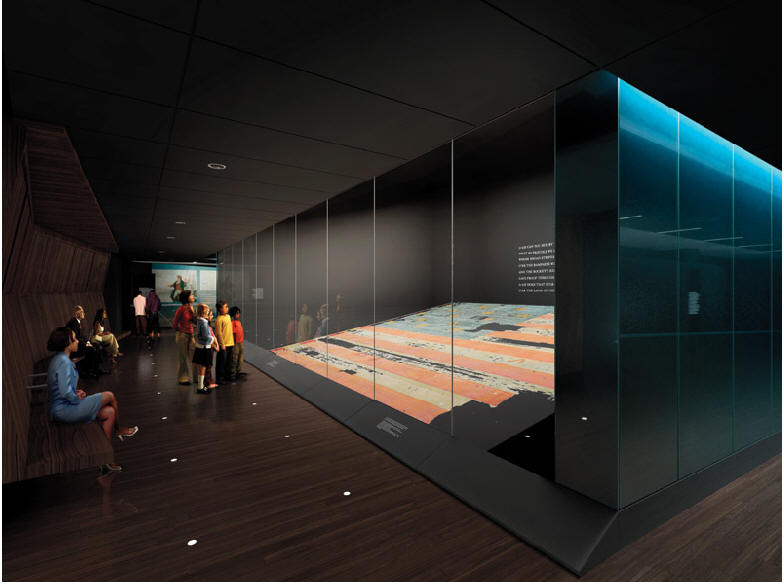

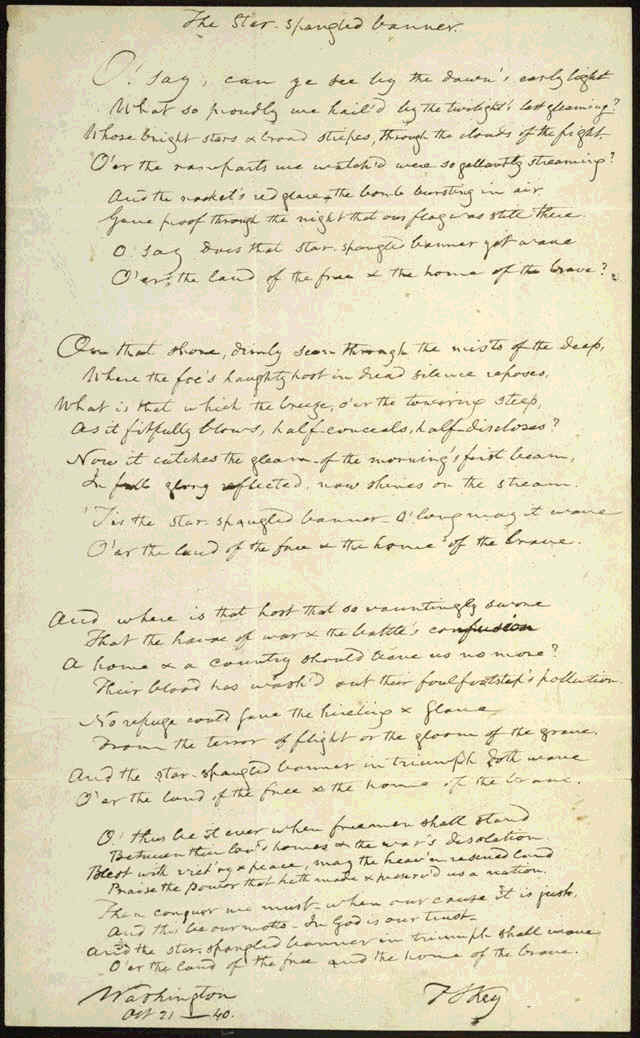

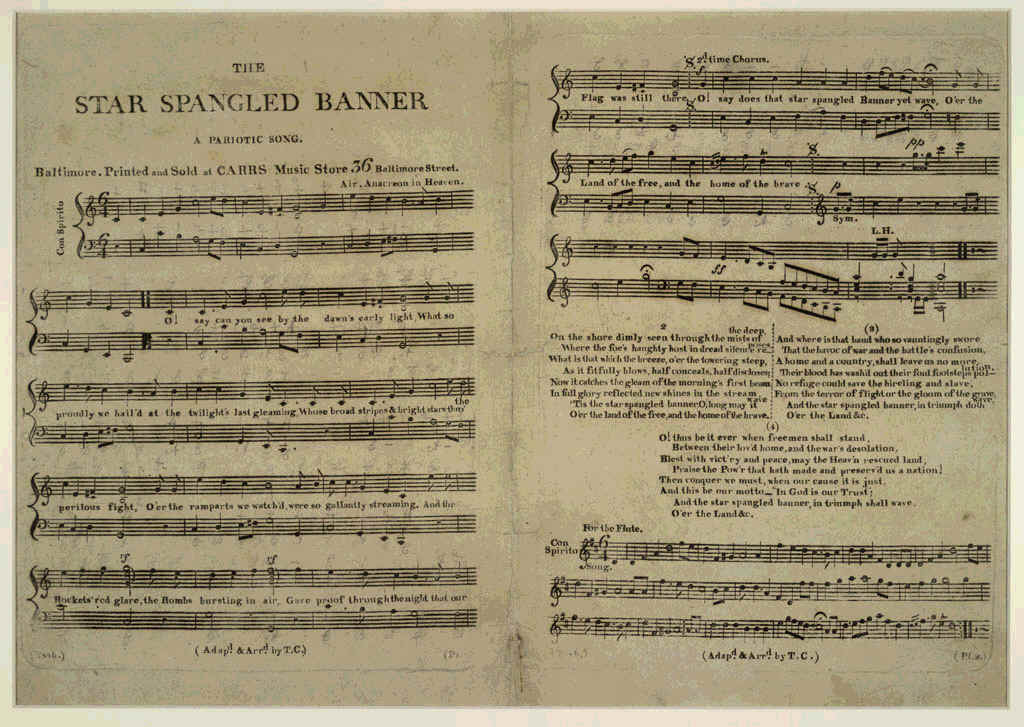

Thrilled by the sight of the flag and the knowledge that the fort had not fallen, Key took a letter from his pocket, and began to write some verses on the back of it. Later, after the British fleet had withdrawn, Key checked into a Baltimore hotel, and completed his poem on the defense of Fort McHenry. He then sent it to a printer for duplication on handbills, and within a few days the poem was put to the music of an old English song. Both the new song and the flag became known as "The Star-Spangled Banner." For his leadership in defending the fort, Armistead was promoted to brevet Lieutenant Colonel and acquired the garrison flag sometime before his death in 1818. A few weeks after the battle, he had granted the wishes of a soldier's widow for a piece of the flag to bury with her husband. In succeeding years, he cut off additional pieces to gratify the similar wishes of others; the flag itself was seen only on rare occasions. When Commodore George H. Preble, U.S. Navy, was preparing a history of the American flag, he borrowed the Star-Spangled Banner from a descendant of Colonel Armistead, and, in 1873, photographed it for the first time. In preparation for that event, a canvas backing was attached to it; soon thereafter, it was put in storage until the Smithsonian borrowed it and placed it on exhibit in 1907. The flag had become a popular attraction; in 1912, the owner, Eben Appleton, of New York, believing that the flag should be kept in the National Museum, donated it to the Smithsonian on the condition that it would remain there forever. Once in its possession, the Smithsonian hired an expert flag restorer to remove the old backing and sew on a new one to prevent damage during display.

The Star Spangled Banner is accessioned into the permanent collection of the United States National Museum. The flag was first loaned to the museum July 9, 1907 by Eben Appleton, grandson of Major George Armistead, the defender of Fort McHenry. In 1912 Appleton decided to make a permanent gift of the flag to the museum. The Star-Spangled Banner remained in the Arts and Industries Building (the old National Museum) as the new National Museum was constructed across the Mall. In 1964, when the Museum of American History opened, the flag was moved to a prominent place inside the museum's Mall entrance, an awe-inspiring testament to our nation's independence.

The Poem O say, can you see, by the dawn’s early light, What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming, Whose broad stripes and bright stars, through the perilous fight, O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming? And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air, Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there; O say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave? On the shore, dimly seen thro’ the mist of the deep, Where the foe’s haughty host in dread silence reposes, What is that which the breeze, o’er the towering steep, As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses? Now it catches the gleam of the morning’s first beam, In full glory reflected, now shines on the stream ’Tis the star-spangled banner. Oh! long may it wave O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave! And where is that band who so vauntingly swore That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion A home and a country should leave us no more? Their blood has washed out their foul footstep’s pollution. No refuge could save the hireling and slave From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave, And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave. Oh! thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand Between their loved homes and the war’s desolation, Blest with vict’ry and peace, may the Heav’n-rescued land Praise the Pow’r that hath made and preserved us a nation! Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just, And this be our motto—“In God is our trust.” And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

The Star-Spangled Banner was born out of the emotions experienced by Francis Scott Key as he watched the bombardment of Fort McHenry during the War of 1812. Key's poem, "Defense of Fort McHenry," came to be sung to the tune of a pre-existing song, "To Anacreon in Heaven," the melody of which is attributed to Englishman John Stafford Smith. The first musical edition was published by Benjamin Carr of Baltimore and titled "The Star-Spangled Banner." With the passage of time the song grew in popularity, and in 1931 an act of Congress made it our official national anthem.

Lyrics:First VerseOh, say, can you see, by the

dawn's early light, Second VerseOn the shore, dimly seen thro'

the mists of the deep, Third VerseAnd where is that band who

so vauntingly swore Oh, thus be it ever when free men shall stand The National Museum of American History traces

American heritage through exhibitions of social, cultural, scientific and

technological history. Collections are displayed in exhibitions that interpret

the American experience from Colonial times to the present. The museum is

located at 14th Street and Constitution Avenue N.W., and is open daily from 10

a.m. to 5:30 p.m., except Dec. 25. For more information, visit the museum’s Web

site at http://americanhistory.si.edu Source U.S. Government Printing Office. The Library of Congress, American Consulate Greece, The Smithsonian Institute |