|

||||||||||||

|

|

The Science of Star Trek

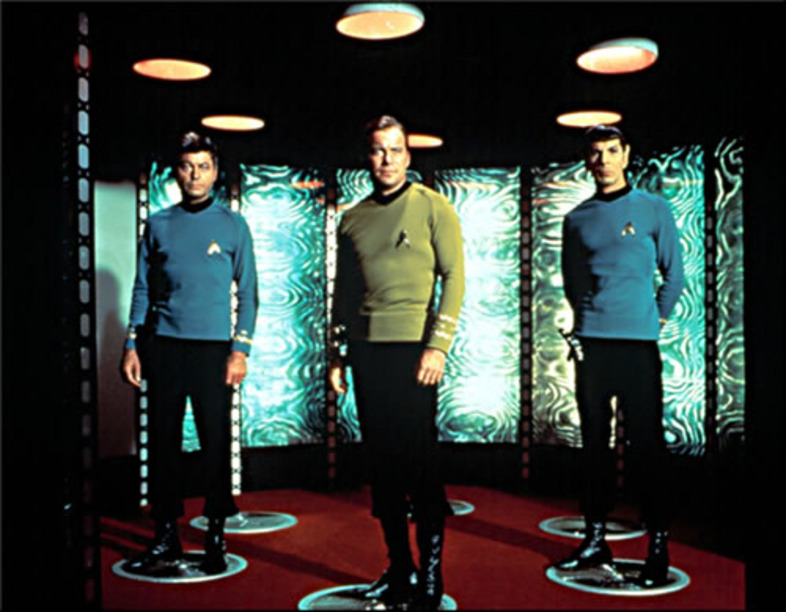

Author: David Allen Batchelor Is Star Trek really a science show, or just a lot of "gee, whiz" nonsensical Sci-Fi? Could people really DO the fantastic things they do on the original Star Trek and Next Generation programs, or is it all just hi-tech fantasy for people who can't face reality? Will the real world come to resemble the world of unlimited power for people to travel about the Galaxy in luxurious, gigantic ships, and meet exotic alien beings as equals?

Well, as for the science in Star Trek, Gene Roddenberry and the writers of the show have started with science we know and s-t-r-e-t-c-h-e-d it to fit a framework of amazing inventions that support action-filled and entertaining stories. Roddenberry knew some actual basic astronomy. He knew that space ships unable to go faster than light would take decades to reach the stars, and that would be too boring for a one-hour show per week. So he put warp drives into the show -- propulsion by distorting the space-time continuum that Einstein conceived. With warp drive the ships could reach far stars in hours or days, and the stories would fit human epic adventures, not stretch out for lifetimes. Roddenberry tried to keep the stars realistically far, yet imagine human beings with the power to reach them. Roddenberry and other writers added magic like the transporter and medical miracles and the holodeck, but they put these in as equipment, as powerful tools built by human engineers in a future of human progress. They uplifted our vision of what might be possible, and that's one reason the shows have been so popular.

The writers of the show are not scientists, so they do sometimes get science details wrong. For instance, there was a show in which Dr. Crus her and Mr. LaForge were forced to let all of the air escape from the part of the ship they were in, so that a fire would be extinguished. The doctor recommended holding one's breath to maintain consciousness as long as possible in the vacuum, until the air was restored. But as underwater scuba divers know, the lungs would rupture and very likely kill anyone who held his breath during such a large decompression. The lungs can't take that much pressure, so people can only survive in a vacuum if they DON'T try to hold their breath.

I could name other similar mistakes. I'm a physicist, and many of my colleagues watch Star Trek. A few of them imagine some hypothetical, perfectly accurate science fiction TV series, and discredit Star Trek because of some list of science errors or impossible events in particular episodes. This is unfair. They will watch Shakespeare without a complaint, and his plays wouldn't pass the same rigorous test. Accurate science is seldom exciting and spectacular enough to base a weekly adventure TV show upon. Generally Star Trek is pretty intelligently written and more faithful to science than any other science fiction series ever shown on television. Star Trek also attracts and excites generations of viewers about advanced science and engineering, and it's almost the only show that depicts scientists and engineers positively, as role models. So let's forgive the show for an occasional misconception in the service of an epic adventure.

So, what are the features of Star Trek that a person interested in science can enjoy without guilt, and what features rightly tick off those persnickety critics? Well, many of the star systems mentioned on the show, such as Wolf 359, really do exist. Usually, though, the writers just make them up! There have also been some beautiful special effects pictures of binary stars and solar flares which were astronomically accurate and instructive. The best accuracy and worst stumbles can be found among the features of the show that have become constant through all of the episodes. Here's a list of the standard Star Trek features, roughly in order of increasing scientific incredibility: The Ship's Computer:Most of the things it does are within the plausible realm of artificial intelligence that computer scientists anticipate. We have auto-pilot functions and navigational systems today, and these are the most used functions of the Enterprise computer. Our computers even approach the ability to interpret spoken orders that the Enterprise computer has. In 400 more years -- the time when Star Trek: The Next Generation is set -- it is reasonable to expect many of the abilities of this computer to really be achieved. Matter-Antimatter Power Generation:This is one of the best scientific features of Star Trek. The mixing of matter and antimatter is almost certainly the most efficient kind of power source that a starship could use, and the way it's described is reasonably correct -- the antimatter (frozen anti-hydrogen) is handled with magneti c fields, and never allowed to touch normal matter, or KA-BOOM! This much is real physics. Let's not bother about the dilithium crystals part . . . sorry, but that's just imaginary.

Impulse Engines:These are rocket engines based on the fusion reaction. We don't have the technology for them yet, but they are within the bounds of real, possible future engineering.

Androids:Well, an important research organization for robotics is the American Association for Artificial Intelligence. At a recent conference on cybernetics, the president of the Association was asked what is the ultimate goal of his field of technology. He replied, "Lieutenant Commander Data." Creating Star Trek's Mr. Data would be a historic feat of cybernetics, and right now it's very controversial in computer science whether it can be done. Maybe a self-aware computer can be put into a human-sized body and convinced to live sociably with us and our limitations. That's a long way ahead of our computer technology, but maybe not impossible. By the way, Mr. Data's "positronic" brain circuits are named for the circuits that Dr. Isaac Asimov imagined for his fictional robots. Our doctors can use positrons to make images of our brains or other organs, but there's no reason to expect that positrons could make especially good artificial brains. Positrons are antimatter! Dr. Asimov just made up a sophisticated-sounding prop, which he never expected people to take literally.

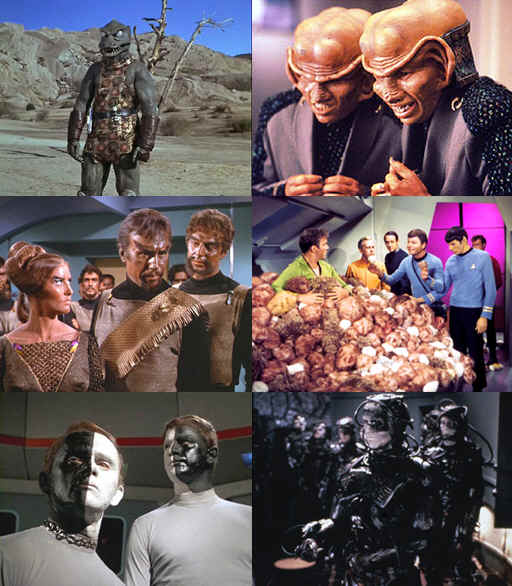

Alien Beings:Most scientists now agree that life probably exists in other solar systems, now that we understand biochemistry a little. The chemical elements for carbon-based life like the lifeforms on Earth are common in the Universe, so maybe lifeforms like ourselves are numerous in the Galaxy. We can imagine all kinds of intelligent creatures, with any number of arms, legs, eyes, or antennae -- maybe a lot smarter than we are. It seems doubtful that humanoid shapes would be as common as the alien races on the Star Trek shows, though. Well, we have to allow the show some concessions to the shapes of available actors. Could half-human/half-alien hybrids ever exist, like Mr. Spock? It seems almost impossible, but with recombinant DNA, our scientists have already created interspecies hybrids. Mr. Spock is not totally beyond biochemical reality, but definitely at the edge. Sensors & Tricorders:

We have vibration sensors, sonar, radar, laser ranging, various kinds of light wavelength detectors and energetic particle detectors, and gravimeters. We also do a little three-dimensional imaging of the interiors of solid objects, like the human body, with magnetic fields and radioactivity detectors. The sensors and tricorders on Star Trek are quite different and more revealing as plot devices than anything we have. But with a stretch of the imagination, the tricorder scan could have today's magnetic resonance imager as its ancestor. The Enterprise's sensors must use the more advanced (and imaginary) "subspace fields,"when it detects far-away objects in space, because the crew never has to wait for signals to travel to a target and return. Not all of the sensors on the show are possible.

Deflector Shields, Tractor Beams & Artificial Gravity:We know how to deflect electrically charged objects using electromagnetic fields, and there are concepts for protecting space travelers from cosmic radiation this way. That's the only physics trick we know that resembles the powerful special effects of the Enterprise shields. We can also make big magnets that have some respectable attraction, and with the right electronic circuits regulating the strength of the magnets, we can imagine towing some kinds of metal objects through space. A beam that is projected at something to attract it is purely imaginary. We don't have any way to create artificial gravity either. Generating artificial graviton particles is imaginable, but there's no way to say how it might be done. Subspace Communications:Mathematicians discovered the concept of a subspace within a space continuum decades ago, and science fiction writers appropriated the term to serve their needs for a super-advanced way to reach other points in space, time or "other" universes. The concept is alive in physics today, in theories that our space-time may have eleven or more dimensions -- three space dimensions and time, plus seven more that are "curled up" within a tiny sub-atomic size scale, where they conveniently explain mysteries of the forces of physics. But Star Trek uses its own unrelated version of subspace, with signals that can travel as fast as the fastest starship. This is just a convenient notion to get messages to Star Fleet and back by the end of a TV show, with no realistic physics behind it. Phasers:

According to the Star Trek: The Next Generation Technical Manual, phasers are named for PHASed Energy Rectification. They are really just spectacular energy blasters, with no detailed physics explanation. The original concept was that they were the next technological improvement upon LASERs. To the extent that they differ from LASERs, they are just fanciful props, descended from generations of blasters in science fiction of de cades past.

Healing Rays:Star Trek's Dr. Crusher shines a healing ray on her wounded patients and the skin or bone heals immediately. That's just a magical medical miracle of the imaginary 24th century. Surgeons today do work with lasers to cauterize or seal some tissues, and repair detached retinas. Some dentists use them, too. Also, there is actually a form of adhesive that can stick human cells together like Elmer's Glue (tm), and synthetic skin for temporarily protecting wounds! But the body's own healing is usually as fast as any other method. On the other hand, there is some evidence that weak electric currents can accelerate healing of bones, so something similar to Dr. Crusher's procedure -- but not instantaneous -- may become possible some day. Replicator:Today, we know how to create microchip circuits and experimental nanometer-scale objects by "drawing" them on a surface with a beam of atoms. We can also suspend single atoms or small numbers of atoms within a trap made of electromagnetic fields, and experiment on them. That's as close as the replicator is to reality. Making solid matter from a pattern as the replicator appears to do, is pretty far beyond present physics. Transporter:

We don't have a clue about how to really build a device like the transporter. It uses a beam that is radiated from point A to point B where it STOPS at just the right precise place -- even passing through some barriers along the way -- and reconstructs the person it carries on the spot. Or it captures a person's pattern, dematerializing him or her, and brings the person to some other point. All of the rematerialized atoms and mol ecules are somehow in the precisely correct positions, with the right temperatures and adhering together just as if the transportee had not been dematerialized. Rematerializing, why doesn't everything fall to pieces if a gust of wind or just normal gravity disturb the reappearing atoms? Nothing in the physics of today gives a hint about how that might be possible. Arthur C. Clarke said, "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic." But we can't assume every magical feat could be accomplished, given sufficiently advanced technology. Holodeck:The same applies to this one. Holograms are apparent images with three dimensional structure. We can't imagine a way to assemble matter in the same way as the light in a hologram. Universal Language Translator:As this is used on the Star Trek shows, it's just an automagical device to enable characters to get through the stories. It would be too tedious and repetitious in a one-hour show for the characters to overcome real language barriers in a realistic manner in every show. The way the Enterprise crew can encounter an alien spacecraft, "hail them on standard frequencies," and establish instant telecommunications on their viewscreens is a preposterous shortcut to keep the plot from faltering. We can certainly dismiss the possibility of such an invention ever being built. Warp Interstellar Drive:This must be the crowning achievement of Federation technology! Despite its fundamental role in the show's plot, it violates known physics to an extent that can't be defended. The detailed explanation of the warp field effect in the ST: TNG Technical Manual only raises mo re questions than it resolves. It is said to involve huge discharges of energy and subspace fields that aren't understood in today's science. However, barring a very unlikely demolition of Einstein's theory by future, revolutionary discoveries in quantum physics, warp drive can't exist. Physicists of today understand the space-time continuum rather well, and there is very good reason to think that no object can move faster than the speed of light. This doesn't stop scientists like the great expert on relativity and quantum theory, Stephen Hawking, from enjoying the fun of the TV series, however. Wormhole Interstellar Travel & Time Travel:These are questionable consequences of some mathematical models for extremely bizarre, artificial arrangements of titanic super-massive objects -- untested imaginary models where Einstein's relativity theory is stretched to its ultimate limits. We don't have any evidence that Einstein's theory is valid in these theoretical cases, and the arrangements of these giant spinning masses don't occur in nature. Conclusion:So, the bottom line is: Star Trek science is an entertaining combination of real science, imaginary science gathered from lots of earlier stories, and stuff the writers make up week-by-week to give each new episode novelty. The real science is an effort to be faithful to humanity's greatest achievements, and the fanciful science is the playing field for a game that expands the mind as it entertains. The Star Trek series are the only science fiction series crafted with such respect for real science and intelligent writing. That's why it's the only science fiction series that many scientists watch regularly . . . like me.

Credit : NASA, PBS |