|

||||||||||||

|

|

Stratospheric Water Vapor is a Global Warming Wild CardJanuary 28, 2010 A 10 percent drop in water vapor ten miles above Earth’s surface has had a big impact on global warming, say researchers in a study published online January 28 in the journal Science. The findings might help explain why global surface temperatures have not risen as fast in the last ten years as they did in the 1980s and 1990s.

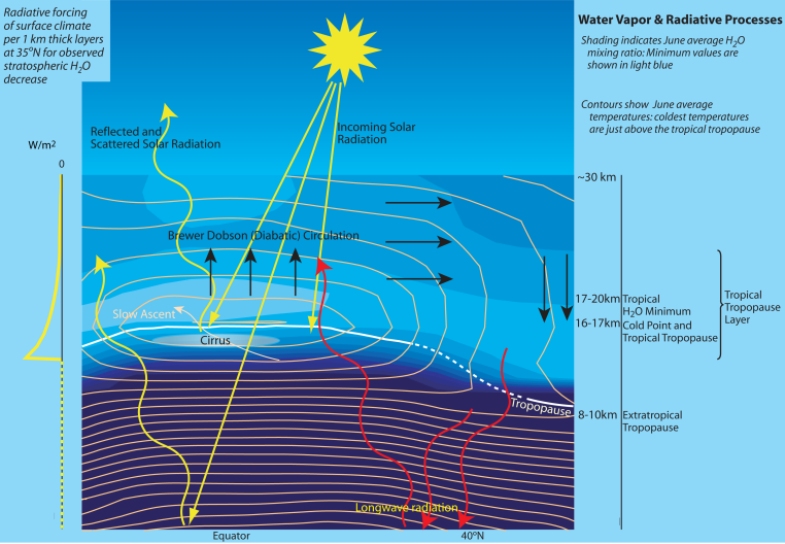

Observations from satellites and balloons show that stratospheric water vapor has had its ups and downs lately, increasing in the 1980s and 1990s, and then dropping after 2000. The authors show that these changes occurred precisely in a narrow altitude region of the stratosphere where they would have the biggest effects on climate. Water vapor is a highly variable gas and has long been recognized as an important player in the cocktail of greenhouse gases—carbon dioxide, methane, halocarbons, nitrous oxide, and others—that affect climate. “Current climate models do a remarkable job on water vapor near the surface. But this is different — it’s a thin wedge of the upper atmosphere that packs a wallop from one decade to the next in a way we didn’t expect,” says Susan Solomon, NOAA senior scientist and first author of the study. “We use the 10-10-10 to describe it,” she said. “That is, a 10 percent change in water vapor, 10 miles above our head, over the past 10 years.” The study also found that from 1980 to 2000, an increase in water vapor sped the rate of warming — the result of an increase in emissions of methane, another greenhouse gas, during the industrial period. Methane, when oxidized, produces water vapor. Why a decrease in water vapor has occurred in the last 10 years is still unknown. Since 2000, water vapor in the stratosphere decreased by about 10 percent. The reason for the recent decline in water vapor is unknown. The new study used calculations and models to show that the cooling from this change caused surface temperatures to increase about 25 percent more slowly than they would have otherwise, due only to the increases in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. An increase in stratospheric water vapor in the 1990s likely had the opposite effect of increasing the rate of warming observed during that time by about 30 percent, the authors found. The stratosphere is a region of the atmosphere from about eight to 30 miles above the Earth’s surface. Water vapor enters the stratosphere mainly as air rises in the tropics. Previous studies suggested that stratospheric water vapor might contribute significantly to climate change. The new study is the first to relate water vapor in the stratosphere to the specific variations in warming of the past few decades. Authors of the study are Susan Solomon, Karen Rosenlof, Robert Portmann, and John Daniel, all of the NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL) in Boulder, Colo.; Sean Davis and Todd Sanford, NOAA/ESRL and the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado; and Gian-Kasper Plattner, University of Bern, Switzerland. NOAA understands and predicts changes in the Earth's environment, from the depths of the ocean to the surface of the sun, and conserves and manages our coastal and marine resources

Credit:NOAA,NASA |