|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

Arctic Wildlife

Birds

Laysan Albatross The Laysan Albatross breeds on isolated islands in the central Pacific Ocean, but is found throughout the northern oceans during all times of the year. They are most commonly seen in the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands flying low over the waves searching for food. Laysan Albatrosses are among the largest of all flying birds, having a wingspread greater than 2m (6 ft), but weighing only 10 kg (22 lbs). Early Aleut and Eskimo hunters apparently preferred albatrosses for their meals because archeologists find hundreds of albatross bones in the remains of old houses and villages along the Bering Sea coast. Laysan Albatrosses are specialized feeders on schooling fish and snatch unwary individuals from just under the surface. Once hatched, albatrosses will return to land only to breed, the rest of their life is spent at sea. They sometimes are seen asleep on the water, but this makes them easy targets for killer whales and stealthy hunters in kayaks; most albatrosses apparently sleep while gliding in the air.

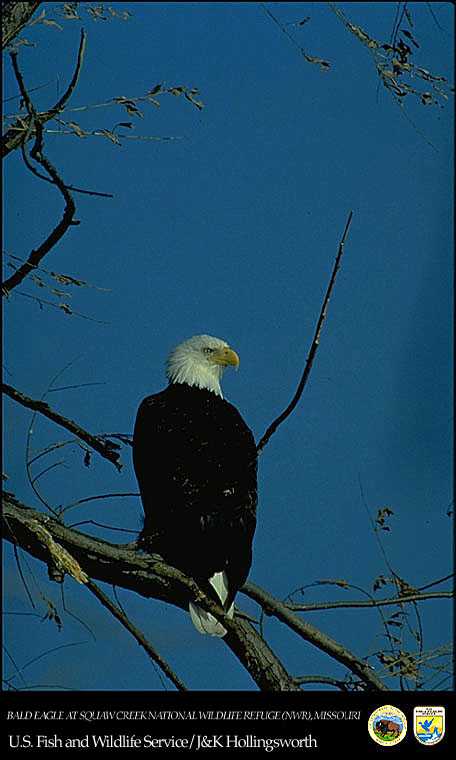

Bald Eagle Bald Eagles are large and dangerous predatory birds of North America. They used to be found throughout the US and Canada, but they are now most commonly seen in the northern forests and Arctic regions. Bald Eagles are very sensitive to disturbance of their feeding and breeding areas by humans, and it is only in isolated or protected regions where they now occur in large numbers. Bald Eagles make very large nests at the tops of trees close to water where they can get fish to feed their chicks. Bald Eagles prefer to catch fish from streams and shallow water by flying low and snatching them out of the water with their feet! Early Eskimo and Indian hunters would look for flocks of eagles to tell them where the salmon were swimming, because eagles have better eyesight than we do. When they see many fish close to the surface they will flock together to catch them. Bald Eagles also will eat dead fish on the shore, and many good places to find them now are near fish canneries and city dumps. Early Arctic people would make traps for eagles using dead fish and a hidden net to trap them. Bald Eagles leave the arctic in fall and migrate south to warmer climates because they find it difficult to find food in winter.

Peregrine Falcon Peregrine Falcons are small hawks most commonly seen in the arctic flying high and fast over tundra and forests looking for food. Peregrines commonly eat small rodents (mice and lemmings) and sometimes eat sparrows and other small birds. Peregrine Falcons breed in small nests hidden on rocky cliffs throughout the arctic, and usually found over land near tundra or meadows. Falcons catch food by diving in the air very fast and stunning their prey. Because they eat so many mice and small animals, they can be exposed to large amounts of toxic chemicals and poisons in the environment. Before we understood how dangerous some insecticides were, Peregrine Falcons became very rare because high concentrations of DDT and other poisons made their eggs brittle and weak. Better controls on these chemicals in the environment helped Peregrine Falcons to breed again by reducing the amount of toxic chemicals in their food.

Ptarmigan Ptarmigan are small chicken-like birds which live year round in the arctic lands, and are found most commonly on tundra hiding in rocks or bushes. They have two different colors of plumage depending upon the season. They are brownish with dark stripes in summer, but completely white in winter. These changes in appearance are so they can hide when they eat. In summer, they blend into the tundra plants and look like shadows; in winter, they look like the snowy ground they walk on. Because Snowy Owls are camouflaged in the same way, Ptarmigan have to be careful when they move around to eat. If they aren't, the owls will catch them! Ptarmigan can fly, but they usually like to walk slowly and eat berries and leaves from the tundra plants

Tufted Puffin Tufted Puffins breed on islands and rocky cliffs in the arctic waters of the North Pacific, which includes the Arctic, Bering, and Okhotsk seas. They are most commonly seen flying near land, coming or leaving the breeding colonies to feed their young. Tufted Puffins are the size of pigeons, but weigh nearly twice as much (1 kg, 2 lbs)! In flight they look like flying cigars, moving very quickly close to water. They feed by diving, then flying under water with their wings in pursuit of small minnow-like fish. Puffins hold the fish in their bills until they return to the nest to feed the puffin chicks. Sometimes a parent puffin will carry a dozen fish carefully arranged head-to-tail in their bills! How do they do that? No one knows, because no one has watched puffins long enough under water. Puffins breed in holes they dig into the ground and build their nests. Puffin chicks will come out only when they are ready to fly; before then they will never see the light or go outside. Puffins breed in colonies, some with only a few nests and some very large. The largest colony is found on Talan Island in the Okhotsk Sea and has more than one million nests!

Snowy Owl Snowy Owls are found only in the Arctic, and are seen most commonly sitting very still on the tundra. Snowy Owls are about the size of a Great Horned Owl but are different in that they will hunt during the day and that they have two different colors of plumage depending upon the season. In summer, Snowy Owls are brownish with dark spots and stripes. In winter, they are completely white. These changes in appearance are so they can hide when they hunt, so that Snow Owls can sneak up and catch the small mice and birds that they eat. In summer, they blend in to the tundra colors and look like shadows; in winter, they look like the snow covering the ground. During the spring breeding season, owls will also feed on eggs of waterfowl, including geese and swans which are very much larger than they are. They have to be very quick to take an egg from a swan! Snow Owls breed on the tundra and are very good at hiding their nests and eggs. The nest is made of dried tundra plants and the eggs look very much like the surface of the tundra. When parents come to incubate the eggs or feed the chicks they will move slowly and carefully so that a fox or raven won't find the nest. Snowy Owls do not fly south in the winter, but will stay wherever there is food to eat. Sea Mammals Polar Bears

Polar bear - Ursus maritimus - on the Beaufort Sea ice in the summer Photographer: Captain Budd Christman, NOAA Corps Polar bears inhabit Arctic sea ice, water, islands, and continental coastlines Biologists estimate their population at 22,000 to 27,000 bears, of which around 15,000 are in Canada.

Class:

Mammalia (Mammals)

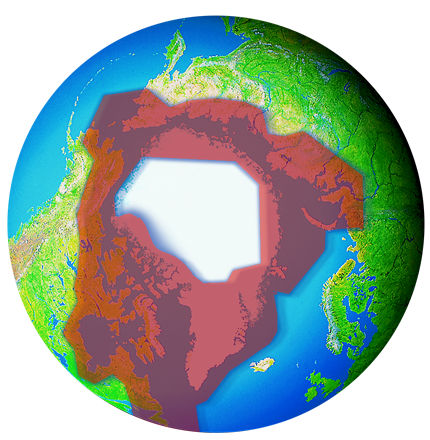

The polar bear, or “Nanuuq,” as the Eskimos call it, lives only in the Northern Hemisphere, on the arctic ice cap, and spends most of its time in coastal areas. Polar bears are widely dispersed in Canada, extending from the northern arctic islands south to the Hudson Bay area. They are also found in Greenland, on islands off the coast of Norway, on the northern coast of the former Soviet Union, and on the northern and northwestern coasts of Alaska in the United States. Some polar bears may make extensive north-south migrations as the pack ice recedes northward in the spring and advances southward in the fall. They also may travel long distances during the breeding season to find mates, or in search of food.

Appearance The polar bear is the largest member of the bear family, with the exception of Alaska’s Kodiak brown bears, which equal polar bears in size. Males stand from 8 to 11 feet tall and generally weigh from 500 to 1,000 pounds, but may weigh as much as 1,400 pounds. Females usually stand 8 feet tall and weigh 400 to 700 pounds, but may reach 700 pounds. Part of the reason the polar bear weighs so much is that it stores about a 4-inch layer of fat to keep it warm. The polar bear has a longer, narrower head and nose, and smaller ears, than other bears. Although the polar bear’s coat appears white, each individual hair is actually a clear, hollow tube. Some of the sun’s rays bounce off the fur, making the polar bear’s coat appear white. During the summer months, adult bears molt, or gradually shed their coats and grow new ones, which look pure white. By the following spring, the sunshine has caused their coats to turn a yellowish shade. Polar bears also sometimes may have a yellowish shade to their coats caused by staining from seal oils. Polar bears live on ice and snow, but that’s not a problem—these bears have some cool ways to stay warm!

The polar bear’s coat helps it blend in with its snow-covered environment, which is a useful hunting adaptation. The polar bear’s front legs appear slightly bowllegged and pigeon-toed, and fur covers the bottoms of its paws. These adaptations help the polar bear keep them from slipping on ice. Feeding Habits Polar bears are mainly meat eaters, and their favorite food is seal. They will also eat walrus, caribou, beached whales, grass, and seaweed. Polar bears are patient hunters, staying motionless for hours above a seal's breathing hole in the ice, just waiting for a seal to pop up. Because the polar bear rarely eats vegetation, it is considered a carnivore, or meat-eater. The ringed seal is the polar bear’s primary prey. A polar bear may stalk a seal by waiting quietly for it to emerge from its blow hole or “atluk,” an opening seals make in the ice allowing them to breathe or climb out of the water to rest. The polar bear will often have to wait for hours for a seal to emerge. Because the polar bear’s coat is camouflaged against the whiteness of the ice and snow, the seal may not see the bear. Polar bears typically eat only the seal’s skin and blubber, or fat, and the remaining meat is an important food source for other animals of the Arctic. For example, Arctic foxes feed almost entirely on the remains of polar bear kills during the winter. Polar bears also prey on walrus, but, because of the walrus’s ferocity and size, bears are usually only successful preying on the young. The carcasses of whales, seals, and walrus are also important food sources for polar bears. In fact, because of their acute sense of smell, polar bears can sense carcasses from many miles away.

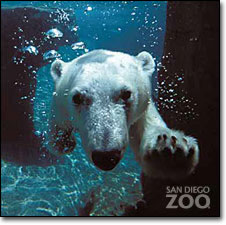

Credit: USFWS Polar bears can cover significant distances on land, but are most agile in the sea. They are excellent swimmers, and can reach speeds of up to 6 mph in the water. They are good divers, too. When being pursued by hunters in open water, polar bears have been known to escape by plunging 10 to 15 feet below the surface and resurfacing a good distance away. They also have been seen swimming 100 miles or more from ice or land.

Credit: Steve Hillebrand / USFWS Reproduction Polar bears reach breeding maturity at 3 to 5 years of age. Males may travel great distances in search of female mates. While breeding usually takes place in April, the embryos may not implant (develop) until the following year, depending on whether the mother has had a stable enough supply of food to sustain herself while allowing her to feed the developing cubs through the winter.

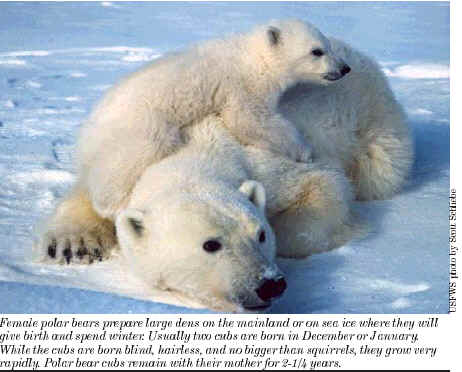

Credit: USFWS In October and November, male polar bears begin to head out on the pack ice where they spend the winter. Pregnant females, however, seek sites on the mainland or on sea ice to dig large dens in snow where they will give birth and spend the winter. The temperature inside the polar bear’s den can be as much as 40 degrees warmer than outside. Usually two cubs are born in December or January. When the cubs first arrive, they are blind, hairless, and no bigger than squirrels. However, the cubs grow rapidly from the rich milk provided by their mother. As soon as spring comes, the mother bear leads her cubs to the coast along the open sea, where seals and walrus are abundant. The mother will fiercely protect her cubs from any perceived danger. The cubs remain with their mother for 2-1/4 years. Because of this, most adult female polar bears breed only every third year. Protection Polar bears have traditionally played an important role in the culture and livelihood of Eskimos and other Native people of the North. They depend on the animals for food and clothing. In the United States, polar bears are a federally protected species under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. This protection prohibits hunting of polar bears by non-Natives and establishes special conditions for the importation of polar bears or their parts and products into the United States. Eskimos and other Alaska Natives are allowed to harvest some polar bears for subsistence and handicraft purposes. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is the federal agency responsible for managing polar bears under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Arctic Circle (Oct. 2003) -- Three Polar bears approach the starboard bow of the Los Angeles-class fast attack submarine USS Honolulu (SSN 718) while surfaced 280 miles from the North Pole. Sighted by a lookout from the bridge (sail) of the submarine, the bears investigated the boat for almost 2 hours before leaving. Commanded by Cmdr. Charles Harris, USS Honolulu while conducting otherwise classified operations in the Arctic, collected scientific data and water samples for U.S. and Canadian Universities as part of an agreement with the Artic Submarine Laboratory (ASL) and the National Science Foundation (NSF). USS Honolulu is the 24th Los Angeles-class submarine, and the first original design in her class to visit the North Pole region. Honolulu is as assigned to Commander Submarine Pacific, Submarine Squadron Three, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. U. S. Navy photo by Chief Yeoman Alphonso Braggs.

A young Polar bear stands up to get a better look at the Los Angeles-class fast attack submarine USS Honolulu (SSN 718) while surfaced 280 miles from the North Pole.U. S. Navy photo by Chief Yeoman Alphonso Braggs An international conservation agreement for polar bears signed in 1976 by the United States, the former Soviet Union, Norway, Canada, and Denmark (Greenland) also provides for cooperative management of polar bears. The Fish and Wildlife Service and the United States Geological Survey’s Alaska Science Center work together to monitor polar bears in Alaska, where they number approximately 4,700, and study their behavior. Cooperative efforts with Canada involve monitoring polar bears in the Beaufort Sea, and the agencies work with the Russian government to monitor the animals in the Chukchi Sea.

Polar bear with cub. Credit: Scott Schliebe/USFWS Another treaty, the “Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Russian Federation on the Conservation and Management of the Alaska-Chukotka Polar Bear Population,” unifies the American and Russian management programs that affect this shared population of bears. Notably, the treaty calls for the active involvement of Native people and their organizations in future management programs. It will also enhance long-term joint efforts such as conservation of ecosystems and important habitats, harvest allocations based on sustainability, collection of biological information, and increased consultation and cooperation with state, local, and private interests. The Fish and Wildlife Service also undertakes education and outreach efforts to inform the public about how polar bears can be protected from over-harvest.

Polar Bear at Cape Churchill (Wapusk National Park, Manitoba, Canada) photo taken by Ansgar Walk

Polar Bears at Risk

In Alaska, demands for oil, natural gas, and other resources have led to some conflicts between polar bears and humans. A number of protective measures have been taken to reduce human activities along the coast in polar bear denning areas. This is when the animals are most sensitive to outside disturbances. For example, oil and gas pipelines and roads have been routed to avoid these areas. The Fish and Wildlife Service also provides expertise to industries on how to minimize conflicts with bears while conducting their operations. Today it is estimated that there are 20,000 to 25,000 polar bears worldwide. With continued cooperative management, these great marine mammals, and the unique arctic environment on which they depend, can be protected for generations to come.

Polar bears range throughout the Arctic in areas where they can hunt seals at open leads. The five "polar bear nations" where the ice bears are found include the U. S. (Alaska), Canada, Russia, Denmark (Greenland), and Norway.

Biologists estimate their population at 22,000 to 27,000 bears, of which around 15,000 are in Canada. In 1973, the five nations with polar bear populations (Canada, Denmark, which governed Greenland, Norway, the U.S., and the former U.S.S.R.) entered into the International Agreement for the Conservation of Polar Bears. Here is what they encounter in each nation:

Scientists analyzing decades of data from Arctic Sea ice recently reported a significant reduction in the thickness of the ice during the last decade. The scientists found a decrease in sea ice all across the Arctic Ocean. Polar bears need sea ice so they can hunt for seals. A retreat and loss of sea ice could make it harder for these animals to get enough food. Pregnant females and those with cubs may be particularly at risk.

Beluga Whale Beluga or "white whales" are not born white. They are grey at birth and get lighter and lighter until at about age six they are completely white. Belugas are one of the three whales that spend all their lives in arctic waters. The other two are the bowhead and the narwhal. Beluga are special among all whales because they can turn their heads. Maybe this is so that they can communicate with each other better! Beluga are very social and make a wide variety of sounds. A group of beluga can be loud! They have been nick-named "sea canaries." Beluga use sound to help them find their prey. They send out a sound which bounces off things in the water and allows them to hear how far away something is. This is called "echolocation." Beluga will work together using this and other techniques to herd fish into shallow water. It has also been reported by native people that beluga whales help each other give birth! They use many subtle forms of communication including a wide variety of facial expressions. Unlike some other whales, beluga have good vision.What they don't have is a dorsal fin, earning them the name "delphinapterus" or dolphin-without-a-wing.

Orca (Killer Whale) The orca or "killer whale" can be found in all oceans of the world. Many are found in the Arctic. The orca is a striking sight, all black with a white underbelly and white around the eyes. It has many sharp teeth that can be up to 5 inches long. These help it to catch and eat its prey. The orca feed on fish, seal, sea otters, walrus and sometimes other small whales. Orcas are very strong swimmers. Aided by their large flippers, they can move through the ocean at up to 25 miles per hour. The orca is quite a social animal. It travels with 5-20 members of its extended family known as its pod. The family has specific calls and even hunts together sometimes. Calves are already eight feet long at birth! Adult males grow to 27 feet and females are usually slightly smaller. You can spot an orca in the water by looking for its large dorsal fin. These fins can be six feet tall. The Tlingit people of Alaska's seacoast create powerful images of the killer whale in their artwork.

Sea Otter Sea Otters are playful animals that spend almost all their time in the sea. They eat, sleep, and even have their babies in the water. In the daytime sea otters float on their backs eating Abalone, their favorite food. To open the Abalone shell they place a small rock on their chest and smash the shell against it. Sea otters are one of the few mammals, beside humans, that use tools. They will use strands of kelp to tie themselves into the kelp beds for a secure night's sleep. They love to frolic with other otters and seals. Unlike seals and walrus, sea otters have no blubber to keep them warm in the cold arctic waters. Air trapped in their fur keeps them warm and bouyant. Oil spills can damage this fine fur and cause the otter to get very cold and die. That is why volunteers cleaned the sea otters so carefully after the oil spills in Alaska. Sea otters also faced great dangers from hunters who wanted their valuable coats. They were hunted so heavily in the 18-19th Centuries that they had to be placed on the U.S. government endangered species list. Now the populations have come back to a large extent, but conservationists would like to continue to protect them. Fishermen would like them off the endangered species list in order to protect the abalone harvest.

Seals Seals swim in Arctic waters eating fish like arctic cod as well as crustaceans and mollusks. Their rear flippers are turned backward. This improves their swimming, but makes it difficult to move around on land because their toes point backwards. Try walking around with your toes pointing backwards! Instead they prefer sliding around on the ice.

One species, the ringed seal, spends most of its time beneath the ice. It digs up through the ice with its strong claws to open breathing holes and must keep pushing it nose through the ice to keep the holes from icing over. This is easier than making new holes, but if they aren't careful a polar bear will see their hole and catch them. Seals are great divers and can stay under water for long periods of time without returning to the surface for a breath. Mature seals mate in the spring. Calves are born in the spring of the following year, and stay with their mothers for a few weeks until they are able to catch prey for themselves. Besides, their soft baby fur is not warm enough to be alone, and they must wait until their white fur has changed to a darker thicker pelt better suited for arctic waters. Seals were over hunted by humans for many years, but now many seal species are protected and can only be caught by native people in the Arctic.

Walrus Everyone knows what a walrus looks like! Its long ivory tusks are used for many things, including protection from attack by polar bears, killer whales and local hunters in kayaks. Walrus are very slow on land because they are so big and clumsy, but in the water they are very fast and strong. They can dive down 300 feet to retrieve their favorite food, clams, from the sea bottom. A walrus can eat 4,000 clams in one feeding! Air sacs in the walrus' neck allow it to sleep with its head held up in the water. Nursing females use this standing position as they nurse. The pups, born approximately every two years, nurse upside down. Walrus will dive into the water at the faintest scent of a human. Walrus numbers were very reduced by commercial hunters until 1972 when the Marine Mammal Act started protecting them. Now only native people in the Arctic may hunt them and the populations have grown in size. Native peoples in the Arctic hunt the walrus for food and put every part of its body to good use. They use the tusks for the delicate art of carving called "scrimshaw." Land Animals

Arctic Fox A well adapted predator, the arctic fox has a gray, or blue coat in the summer and a thick, warm white coat in the winter. Its foot pads are also densely furred so that the animal can travel on the snow and ice hunting for prey. The arctic fox feeds on lemmings, voles, squirrels, birds, bird eggs, berries, fish and carrion. In the winter the fox will follow polar bears hoping to eat the bear's leftovers. The arctic fox has to be very sly or it will become the polar bear's lunch! Luckily its white coat makes it hard for the polar bear to spot. The arctic fox burrows into the ground or snow for protection from the arctic cold. It will create a store of food over the summer months and freeze it in the permafrost. Pups are born in dens every spring. The female fox has a litter of 6-12 and the family will stay together through the summer. The male fox brings food for the family and guards the den

Caribou & Reindeer Reindeer and Caribou look different, but they probably are the same species. Caribou are large, wild, elk-like animals which can be found above the tree-line in arctic North America and Greenland. Because they can live on lichens in the winter they are very well adapted for the harsh arctic tundra where they migrate great distances each year. Caribou cows and bulls both grow distinctive antlers and bull antlers can reach 4 feet in width! A Caribou calf can run within 90 minutes of its birth. It must do this to keep up with the migrating herds.

Reindeer are slightly smaller and were domesticated in northern Eurasia about 2000 years ago. Today, they are herded by many Arctic peoples in Europe and Asia including the Sami in Scandinavia and the Nenets, Chukchi and others in Russia. These peoples depend on the reindeer for almost everything in their economy including food, clothing and shelter. Some Nenets even keep reindeer for pets! Reindeer were introduced into Alaska and Canada last century, but most attempts failed. Native peoples in these countries still prefer to hunt caribou rather than herd reindeer. Reindeer and caribou have unique hairs which trap air providing them with excellent insulation. These hairs also help keep them buoyant in the water. They are very strong swimmers and can move across wide rushing rivers and even the frozen ice of the Arctic Ocean!

Lemming Lemmings are small mouse-like animals that live in the tundra. In summer they are brown, but in winter they are all white. Their white coats help them to hide from the snowy owl and other predators who depend upon them for food in winter. Lemmings make simple burrows in the tundra during the summer, and they can make it very difficult to walk around. Especially when you fall through them up to you knees! In winter, they hide from the coldest weather in shallow burrows in the snow. Lemming populations shrink and swell depending on how many plants and berries are available. One type of lemming, the Scandinavian lemming, migrates in a huge group when food becomes scarce. They will run in one direction through meadows, woods and towns. If they come to a large body of water they will swim and swim looking for land. The stories about lemmings jumping off cliffs are a myth. Other types of lemmings simply move away when the food gets scarce.

Muskox Muskox are large animals that look a lot like bison, but have wool like sheep. Their long brown wool hangs almost to their feet! If you visit Alaska you will find woven musk ox wool scarves at many tourist shops. Most of the arctic tundra was host to the musk ox long ago. Neolithic hunters hunted them almost to extinction. Today they can be found in northern Canada roaming wild, and on farms in Unalakleet, Alaska where they are raised for wool. Muskox roam wild in herds of 10-20 individuals. When they are threatened by a wolf their main predator (other than man) they will form a circle around their young to protect them. Muskox have been known to scoop up wolves with their horns, hurl them into the air and then stomp them under hoof. Although this may seem violent, muskox are mainly peaceful animals who eat only plants. Their name comes from the musky smell of their urine which is especially strong in mating season. Muskox usually bear one calf every two years.

Credit: NOAA,USGS,USFWS, Smithsonian |